|

SwalwellThe former Crowley works in the 19th century |

| Beginnings | Brewing | Agriculture | Derwenthaugh | Coalmining | Derwenthaugh Staiths | Engineering, etc. | Papermaking | Today |

|

Home Origins Industry Railways Buildings Buildings 2 People Sport Memories Memories 2 Memories 3 Memories 4 Today Links |

IndustryClick here for industry slideshowBEGINNINGS - IRON AND STEELIt is likely that there was little real industry in Swalwell, apart from some coal mining and the keelmen's trade, until 1707 when Ambrose Crowley* established a large ironworks in the village. The locations at Swalwell, and also at Winlaton and Winlaton Mill, were determined by the availability of power, raw materials and transport and a market for the products. The district had a ready source of water power from the River Derwent and was conveniently located for the Baltic trade-its main source of iron was Sweden, had good transport links by river and sea, and a growing market for the type of goods which the factories produced, especially with the Admiralty. Crowley's supplied the Royal Naval Dockyards with various articles such as anchors, chains and cables and later had contracts with the Admiralty during the time of the Napoleonic Wars. The Swalwell works, occupying four acres, were the greatest on Tyneside early in the nineteenth century, and were said to be the largest ironmaking concern in Europe between 1725 and 1750. They prospered especially in times of war when their products were in great demand. But the economic advantages Crowley's once possessed were much reduced in the 19th century as new markets appeared which could be served better from the Midlands, and Swedish and Russian iron ore was supplanted by the convenient availability of English ore. Initially, Crowley was not involved in preparing the iron for the later stages of manufacture of articles, but soon pig iron was being converted into bar iron in forges and thence into rod iron or steel, all using the water power readily available from the Derwent. High quality steel was produced and iron anchor-making was a speciality. Crowley's Swalwell forge was later famous for its chain-making skill, large and heavy anchor chains being produced here.The canals favoured the new centres of production further south and technical advantages and competition both locally and elsewhere completed the conditions which led to the decline of the Crowley's works and eventual closure about 1853. By that time Crowley ownership had ceased and the establishment was called Crowley Millington's. The works were sold to Powe and Fawcus of North Shields in 1863 for £780, auctioned in 1870, and later leased to Ridley and Co. who established a steel foundry on the site in 1893 with forges, hammers, smiths' shops and machine shops. They finally closed in 1911. The paper mills of Wm. Grace and Co., later known as the Northumberland Paper Mills also occupied part of the Crowley site in the late 19th and early 20th century. The large chimney in Swalwell, shown on the Home Page, remains as a landmark on the Crowley site. It was built as part of the paper mill which dates from late Victorian times. The precise date is unknown. A forge existed on the Derwent near the Dam Head using water power and called Swalwell High Forge, chain-making being their main activity. There was a gasometer here too in the late 19th century. The Swalwell Visitor Centre is situated on this site. * N.B. There is more about Ambrose Crowley and the iron works on the People page. |

BREWING

|

|

AGRICULTURE Before any industry appeared, apart from some coal being taken from outcrops, that is from near the surface, and before deep mining was established, agriculture was predominant. Until fairly recently there were farms at Millers Lane, (Oxley's, see picture), and at Millers Bridge, both of which farmed the fields in and around Swalwell. Millers lane was the site of a water-powered mill. The fields are now either built on or are simply grassed over though a few of the farm buildings remain. South west farm was Tailford's, then Rutters, then Smiths. South West Farm Cottage at Millers Bridge is still inhabited, but Oxleys farmhouse has become derelict since the house became empty and is now part of the scrapyard. Until the 1960's cows were kept in the byres along Millers Lane. Horses are still grazed on the field between the Western By Pass and Market Lane near the fire station. Before any industry appeared, apart from some coal being taken from outcrops, that is from near the surface, and before deep mining was established, agriculture was predominant. Until fairly recently there were farms at Millers Lane, (Oxley's, see picture), and at Millers Bridge, both of which farmed the fields in and around Swalwell. Millers lane was the site of a water-powered mill. The fields are now either built on or are simply grassed over though a few of the farm buildings remain. South west farm was Tailford's, then Rutters, then Smiths. South West Farm Cottage at Millers Bridge is still inhabited, but Oxleys farmhouse has become derelict since the house became empty and is now part of the scrapyard. Until the 1960's cows were kept in the byres along Millers Lane. Horses are still grazed on the field between the Western By Pass and Market Lane near the fire station.

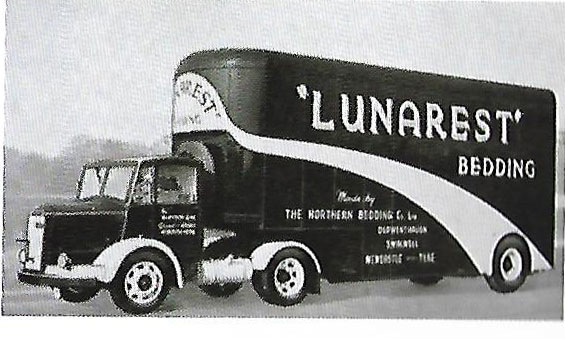

DERWENTHAUGHThe Blaydon Main Colliery, which originally opened in 1828 and reopened again in 1853, had its own wagonway to Blaydon Main staiths at Derwenthaugh, with a link to the Redheugh branch railway at Blaydon Main Junction. The pit, called the Hazard, was situated on the site of Blaydon swimming baths, and closed in 1921. The Garesfield and Chopwell Railway had its Garesfield Staith, later enlarged in 1899 under Consett Iron Co. ownership. The Garesfield Colliery, railway and staiths had come into Consett Iron Co. ownership from 1889. The staiths were further extended in 1912-13 with two berths. Coke ovens existed next to the railway near to Raines Delta works and also next to the Blaydon Main staiths. With the coming of the railway, industry began to appear at nearby Derwenthaugh with a cokeworks*, firebrick works, situated on the west bank of the Derwent, adjacent to the staiths, and the Delta ironworks, see picture, later known as Raine and Co. (1891 - 1990). The brothers Benjamin and George Raine took over the old Crowley works at Winlaton Mill in 1885 and later moved to Derwenthaugh, producing colliery (girder) arches and other materials for the mining industry, light railway track, fish plates, iron and steel bars, angles and other general sections and rivet iron for ships.  The First world war brought a big increase in business and extra furnaces and presses were installed . In the Second World War they employed 800 men, but in the 'fifties and 'sixties traditional markets in the shipbuilding and mining industries waned, leading eventually to the end of Raines. They made steel sections for the National Coal Board, earth moving, tractors, and the forklift industries as well as specialised steel sections for general trade use. The Watermark office development which includes ITV Tyne Tees Television occupies part of the site. The Northern Bedding Company (Lunarest Bedding) premises were located near the railway junctions on the west side of the Derwent.

* N.B. These cokeworks are not to be confused with the cokeworks at Winlaton Mill, also known as Derwenthaugh cokeworks. Back to top of page |

DERWENTHAUGH STAITHS Finally, at Derwenthaugh the coal staiths, (see pictures), were busy with colliers taking coal, much of it destined for the power stations on the Thames, and with large exports of blast furnace coke to Scandinavia. They remained in operation until 1960. The staiths were rebuilt in the late 19th century aand there was a major rebuilding and extension in 1913 as coal exports increased. Two berths existed, capable of taking ships of 9000 tons. Originally owned by the Consett Iron Company, ownership of the statihs was transferred to the National Coal Board on nationalisation of the coal industry in 1947. The waters at Derwenthaugh were dredged to a depth of thirty feet in the 1950's. Alongside the staiths there were four big tanks for the storage of liquid tar and creosote.

The staiths were established early in the eighteenth century and shipped coal from the Whickham, Spen, Thornley and Pontop areas. In 1794 about 62,000 chaldrons of coal moved along the wagonways leading to the staiths. A chaldron was 53 cwts (i.e. 2 tons 13 cwts) or 2.69 tonnes. Over 600 men and boys and about 400 horses were employed in this undertaking, and 200 keelmen ferried the coal down river to the waiting colliers below the Newcastle bridge. A keelboat carried about 21 tons and the coal was shovelled directly from the keel into the ships hold -no mean feat when the colliers became larger and the hatches were several feet above the keel. Keels also took the ship's ballast carried on the return trip to aid stability, and dumped it in the river, contributing to the silting up of the Tyne in the bad old days before the Tyne Improvement Commission took over the management of the river from Newcastle Corporation who had sadly neglected it. When the river was improved and the old Georgian bridge replaced by the Swing Bridge, the keelmen were no longer needed as colliers could come further up river and the coal was loaded directly into them while they lay alongside at the staiths.

Finally, at Derwenthaugh the coal staiths, (see pictures), were busy with colliers taking coal, much of it destined for the power stations on the Thames, and with large exports of blast furnace coke to Scandinavia. They remained in operation until 1960. The staiths were rebuilt in the late 19th century aand there was a major rebuilding and extension in 1913 as coal exports increased. Two berths existed, capable of taking ships of 9000 tons. Originally owned by the Consett Iron Company, ownership of the statihs was transferred to the National Coal Board on nationalisation of the coal industry in 1947. The waters at Derwenthaugh were dredged to a depth of thirty feet in the 1950's. Alongside the staiths there were four big tanks for the storage of liquid tar and creosote.

The staiths were established early in the eighteenth century and shipped coal from the Whickham, Spen, Thornley and Pontop areas. In 1794 about 62,000 chaldrons of coal moved along the wagonways leading to the staiths. A chaldron was 53 cwts (i.e. 2 tons 13 cwts) or 2.69 tonnes. Over 600 men and boys and about 400 horses were employed in this undertaking, and 200 keelmen ferried the coal down river to the waiting colliers below the Newcastle bridge. A keelboat carried about 21 tons and the coal was shovelled directly from the keel into the ships hold -no mean feat when the colliers became larger and the hatches were several feet above the keel. Keels also took the ship's ballast carried on the return trip to aid stability, and dumped it in the river, contributing to the silting up of the Tyne in the bad old days before the Tyne Improvement Commission took over the management of the river from Newcastle Corporation who had sadly neglected it. When the river was improved and the old Georgian bridge replaced by the Swing Bridge, the keelmen were no longer needed as colliers could come further up river and the coal was loaded directly into them while they lay alongside at the staiths.On 16 June 1951 there was a big fire at Derwenthaugh Staiths with twenty fire engines in attendance, threatening nearby oil storage tanks and resulting in much destruction and closure of the staiths for some time. They were repaired, using concrete instead of wood, and re-opened in January 1953, although parts were no longer used and these were dismantled in 1955. The remainder continued for a few more years before final closure on 23 March 1960. A short section of the lower part of the staith still exists. The Evening Chronicle reported :"Flames Wreck staiths. Flames which put Derwenthaugh staiths completely our of action on Saturday night were stopped by firemen after they had run to within 50 yards of storage tanks holding a million gallons of creosote and tar. Police stood by ready to evacuate families from the nearby Bute Buildings. Acetylene cylinders, which had been left on the staiths by workmen, exploded with such violence that ceilings in Bute Buildings were brought down, while women and children dashed from their homes for safety and twisted metal was hurled more than a hundred yards. There were no casualities. The staiths, which normally load 4000 tons of coal daily on to London-bound coasters, will be completly out of action for an indefnite period, said Mr. William Welsh, National Coal Board area general manager. Pits in the area, however, will not be affected. Units from Northumberland and Durham, Newcastle and Gateshead Fire Brigades battled with the blaze for two-and-a- half hours and a hundred yards of elevated railway leading into the staiths was completely destroyed." Various methods were used to transfer the coal to the ships, known as colliers. At first the coal would go from staith to keel and thence to the collier, then with the advent of the wagonway a hinged spout or chute was used to move the coal from the early railway wagons to the keel or collier, but as railways developed it was superseded by the coal drop with its system of counter balances, whereby a loaded wagon would depress the balance and hence be lowered to the deck of the ship, the empty wagon being raised again to the top of the staith by the counterbalancing weights. This method was not suitable for use at Derwenthaugh while the obstacle of the Georgian bridge remained at Newcastle preventing ships coming further up river. Another method was the wagon drop where the wagon would be lowered to the ship's deck from the staith, the wagon door underneath was opened and the coal poured into the ship's hold. Finally, a more sophisticated gravity spout method was eventually used at almost all the north-east staiths, speeding up loading and helping to minimise time spent in port. The wagon on top of the staith had its bottom doors opened and the coal poured directly down a chute into the hold. It was important not to break up the coal into smaller pieces at one time, as larger lumps were thought more desirable.

Ships - the ColliersThe word staiths (sometimes spelt staithes), occurs in a demise from the Prior of Tynemouth in 1338 AD. At its peak in 1923, 23 million tons of coal was shipped from the Tyne staiths, but this was down to just 4 million tons by the 1960's. The collier pictured on the right at Derwenthaugh in the 1950's is the Chessington, one of many ships owned by the South Eastern Gas Board. This ship of 1720 tons (GRT) was built at Burntisland on the River Firth in 1949 and supplied coal to the gas works south of the Thames from then until it was scrapped in 1967. Some names of colliers which loaded coal at Derwenthaugh between 1950 and 1954 are the Cerne, Chessington, Firelight, Fireguard, Fulham 3, Fulham 10, Kennedy, Pompey Power, Pompey Light, Queenworth, Rattray Head, Sir Leanard Pearce, and Wimbledon. Most of the coal went to power stations on the Thames and some south coast ports to serve the demand for power in the London and southern England areas, although much coal from the Tyne went abroad, especially for bunkers when ships were steam powered from coal-fired boilers. [for further details see Black Diamond Fleets, an account of the north east coast collier fleets of GB 1850-2000 by Norman L. Middlemass, published July 2000 by Shield Publications of Newcastle. A copy is held by Gateshead Library]. One February evening in 1925 a seaman from South Shields lost his life coming aboard his ship via another ship lying alongside his when the horizontally laid ladder between the two ships tipped over and pitched him into the water. A shipmate dived in in an attempt to save him but to no avail as he had struck his head while falling and he drowned.Trimmers and Teemers Trimmers and teemers carried on their unusual calling at the staiths. Teemers were responsible for opening the trapdoors at the bottom of the railway wagons which were shunted onto the top of the staiths and positioned over hoppers. The chocks which locked the hinged flap in the bottom of the wagons were hammered out and the coal or coke fell into the hoppers linked to the spouts directed into the ship's holds. The spouts were raised or lowered according to the height of the ship out of the water with the tide using a hand windlass. When the ship was so high out of the water as to make the use of spouts impractible, then conveyor belts were used. Some Derwenthaugh staiths workers are shown in the picture.

Trimmers and teemers carried on their unusual calling at the staiths. Teemers were responsible for opening the trapdoors at the bottom of the railway wagons which were shunted onto the top of the staiths and positioned over hoppers. The chocks which locked the hinged flap in the bottom of the wagons were hammered out and the coal or coke fell into the hoppers linked to the spouts directed into the ship's holds. The spouts were raised or lowered according to the height of the ship out of the water with the tide using a hand windlass. When the ship was so high out of the water as to make the use of spouts impractible, then conveyor belts were used. Some Derwenthaugh staiths workers are shown in the picture.The trimmers had the job of levelling off the coal in the holds and shovelling it evenly to the sides to ensure the ship's stability, it being necessary to keep it on an even keel with no list. The safety of the ship depended on their skill and the ships' officers would then check that there was a proper distribution of the cargo between the holds and that the ship was trimmed to the requirements of the Plimsoll Line. Trimmers worked for both the shipowners and the owners of the staiths, hence the good pay, or obtained work through an agent, and their job was tough and dirty, and usually done from a kneeling position once the coal had been teemed into the hold. There was always the danger that a loaded wagon would overshoot the end of the staiths and shed its load onto the ship below. Hence trimmers were better paid than the teemers and the more ships they loaded the better was their pay. On 4 June 1951 The Journal (Newcastle) reported that 80 of the 620 trimmers in north east ports were to be made redundant as trimming had become easier. This would delay promotion of teemers, though there were to be only 30 actual redundancies, to be reabsorbed as vacancies occurred. Trimmers jobs were, however, often the preserve of certain families and 'outsiders' may have found it difficult to gain entry. Both teemers and trimmers worked in gangs. There were also some staiths on the east side of the Derwent in the 18th century, together with some lime kilns. These are shown on an old map dated 1718 held in the Tyne and Wear archives at Newcastle. Back to top of page |

TODAYIndustry in Swalwell today has become much less dirty and employs far fewer workers. Bespoke Concrete Products Ltd. recently vacated the Crowley site, Stanley's Recycling, a scrap yard, is on the old Henry Pit yard, while Metro Radio until 2005 occupied the former Ellis office building. There is some light industry, a joiners, a double-glazing firm, a private hire coach company, printers, computer services and two small industrial estates, one near the old station site, the other at the Sands behind Crowley's site. At Derwenthaugh, the former industries have all gone, though trains still pass over the railway bridge and the Delta works is the site of extensive office buildings called The Watermark, including the new (2005) home of Tyne Tees Television.Back to top of page Previous........Next |